Do we have free will or is the world deterministic? It is time to ask a better question….

- Jeff Hulett

- Feb 19, 2024

- 14 min read

Updated: Jan 16

Much has been written about the question of free will vs. determinism. There is increasing evidence that our world is deterministic and outcomes are wired from our past. However, our intuition, experience, and culture suggest we have some free will to make different decisions. But do we? Even more importantly, are we asking the correct question?

After exploring the free will vs. determinism question, we conclude that it is the wrong question. The correct question centers on making the most of our choices today.

Definitive Choice is a resource suggestion to help us make the best judgments.

About the author: Jeff Hulett is a career banker, data scientist, behavioral economist, and choice architect. Jeff has held banking and consulting leadership roles at Wells Fargo, Citibank, KPMG, and IBM. Today, Jeff is an executive with the Definitive Companies. He teaches personal finance at James Madison University and provides personal finance seminars. Check out his new book -- Making Choices, Making Money: Your Guide to Making Confident Financial Decisions -- at jeffhulett.com.

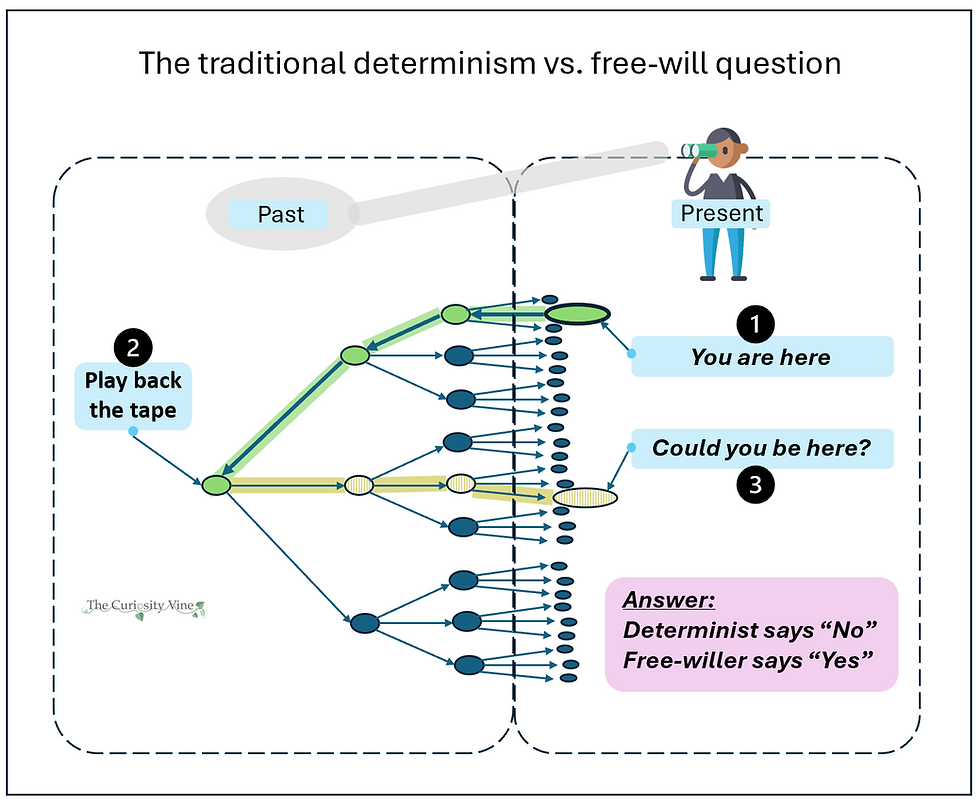

Brian Klaas, a professor at the University College London and an Atlantic magazine contributor, asks a thoughtful free will vs. determinism question. That is, “If you could rewind your life to the very beginning and press play, would everything turn out the same?” [x] This is like rewinding a tape where the past is a single tape but the future is potentially a choice of many tapes. Determinists, like Stanford University neuroscientist Robert Sapolsky, believe we would end up on the same tape path and with the same outcome even if we rewound the tape to some point in the past. [iii] Our nature and nurture environment is so powerful that we have no choice but to go down the same path. In fact, determinists generally believe choice is an illusion, generated as a protective feature from our brains’ evolutionary biology.

Alternatively, free-will folks believe we can end up on different paths and with different outcomes based on the application of our free will. So to a free-will person, choice is real and we can impact our paths and outcomes. Our culture, especially Western culture, creates deep-seated expectations of personal responsibility originating from their free will. As an example, The American form of government is based on free will. The United States Declaration of Independence unambiguously states:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

Think of these "unalienable rights" as choices generated from free will. For example, Americans may choose to speak, assemble, pray, report, and petition the government as per the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Most importantly, within reason, Americans are free to choose how they express these unalienable rights. As an ironclad cultural doctrine, people are expected to make their own pursuit-of-happiness decisions. Free will is popularly considered one of the most precious rights we have in a free country. Many other countries have some form of free will integrated into their culture and constitutions.

For a deeper dive into free will, please see Solving the Decision-making Crisis: Making the most of our free will

The free will perspective is supported by science and philosophical schools. For example, behavioral psychologist Carol Dweck considers the "growth mindset" as the key to unlocking the probabilistic future. [iv] Her approach includes overcoming the challenges of the "fixed mindset" associated with determinism. A core tenet of the Stoic Philosophy is called the "dichotomy of control" [v] and is found on 3 levels:

High influence: Our choices and judgments. To a stoic, this is our free will.

Partial influence: Health, wealth, relationships, and behavior outcomes flowing from our and others' choices and judgments.

No influence: Weather, environment, genetics, and most other environmental factors.

Anil Seth is a cognitive and computational neuroscience professor at the University of Sussex. Dr. Seth’s research conclusions [vi] align with the ancient Stoics’ Dichotomy of Control framework:

“[Free will] is a freedom to act according to our beliefs, values, and goals, and to do as we wish to do, and make choices according to who we are.”

The essence of the free will vs. determinism debate is this:

To evaluate the free will vs. determinism question, we must rewind the tape of our lives. Thus, the evaluation of free will vs. determinism is a backward-facing question. Whereas our choices, regardless of the degree to which free will and determinism impact us, require us to face forward. Choice requires us to make predictions about the uncertain future. They are somewhat related but entirely different questions. As discussed next, decision-making must consider information understood in the present to forecast the future. This difference in forward vs. backward time perspective means the question of free will vs. determinism is the wrong question.

Why the free will vs. determinism question is the wrong question.

“Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards.”

― Søren Kierkegaard

Please consider the outcomes of our decisions as an information and uncertainty question at the point a decision is made. Today, those decision-makers have an incomplete set of information about the future. Thus, decision-makers must do their best to forecast based on their understanding of the benefits they desire from that decision. The perceived benefits are impacted by our deterministic environment. Economists call the components of those benefits “preferences” and the aggregation of those preferences as one’s decision utility.

It is our assessment of our benefits or utility that has wild volatility. The essence of our wild volatility is what behavioral psychologists and behavioral economists call a “failure of invariance.” A failure of invariance is a term with a rich history. Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman suggests a human failure of invariance is at the core of why individual rationality is both situationally and individually variant. [xi] So, not only will any two people have different perspectives on their rationality, but the same person will also vary in their definition of rationality across different but apparently identical situations. A failure of invariance challenges the traditional concept of rationality as a single point. The new definition of rationality indicates that it is user-defined and based on varying situations and individuals. [xii] F.A. Hayek, the economist and Nobel Laureate, suggests the way people utilize knowledge is the most basic problem of a rational economic order. Hayek said: "It is a problem of the utilization of knowledge not given to anyone in its totality."

For a deeper dive: Please see the article How behavioral economics redefined rationality

It is acknowledged that our world has deterministic features based on physics such as Einstein’s famous Special Theory of Relativity equation -> E= MC^2 or Newton’s Second Law of Motion equation -> F=MxA, and many others. Also, our past nature and nurture environment has a massive influence on the availability of and the challenge to make certain decisions. Sapolsky does a great job describing those challenges.

However, and this is the essential point, how we experience the world, over time, is as if the world is indeterministic so long as the agents act with wild volatility. As an individual agent in the highly complex and information-incomplete world, the best that can be hoped for is that they make the best decision at the time the decision needs to be made.

As a thought experiment, let us say you could play back the tape to an exact moment in the past. Would we make the same decision and would the world turn out the same? Without any more information and with the same decision processes - a determinist would argue we would not make a different decision and the world would turn out the same.

At that point, the deterministic features of that world would have been identical. Let’s call our played-back world ‘Universe A.’ Now, what if we could clone Universe A? We call this cloned world Universe B. In both cases, Universe A and Universe B start at the same tape play-back point with identical deterministic features. In the next moment of our two cloned worlds, those worlds will diverge because of that wild volatility. This occurs because, in that next moment, Universe B will have small, randomly occurring differences from Universe A. Those small, random differences could be a butterfly that flapped its wings a little differently, that we woke up a little bit earlier as compared to the other universe, or that one more person in Universe A randomly decided to read this article.

In two different universes with the same starting point and deterministic features, uncertainty and wild volatility will cause Universe A to vary from Universe B at the next point in both those universes’ future. The differences between the universes may be small, but over time chaos theory tells us their differences will grow substantially. Those two universes are metaphors for different people and different situations of the same person as found with wild volatility. We can track back our current world to identify the past deterministic features that sculpted our current world. However, it is the beautiful, uncertain, and contingent current moment inclusive of deterministic features that leads into a future world where we must behave as if it is indeterministic.

So, the degree to which the world is deterministic or we have free will is the wrong question. I propose the correct question is -- How can people behave in the decision moment to make the best decision, given both their priors and their opportunities? In this case, we do not have perfect information and we need to make the best decision we can TODAY. Then, in the moments that follow, we will need to make varying decisions because wild volatility ensures those future moments include uncertainty. Part of this is recognition of what Buddhists call "emptiness." This is the idea that we are the sum of all those around us. Effectively, our existence is only a reflection of the world around us. We are an empty, ever-changing vessel crafted by our impermanent environment.

The Empty Spot - A Buddhist “Emptiness” Metaphor: Imagine all the people you know, and the different elements of your environment are pieces of a mosaic. The pieces start in a jar near an empty canvas. The canvas represents the entire scope of your life. All the things that make you "you" will be found somewhere on that canvas. Over time, those pieces get poured out of the jar and fall, some haphazardly and some with purpose, to affect that canvas. But unlike paint, the pieces never dry to become fixed. Your life’s mosaic pieces change – some slowly and some more rapidly. The jumble of moving pieces of your life leaves an empty spot in the middle of the canvas. That empty, ever-changing spot is you.

This Buddhist approach is descriptive of wild volatility. That is, we cannot help but be impacted by the wild volatility of the world around us. Since all those around us are subject to wild volatility, then we must have a way to respond that makes the most of those fluid and dynamic situations. Our choices are our response to wild volatility and ultimately influence others and our own future.

To summarize, our choices:

Our choices are based upon an impermanent reflection of those around us -> Buddhism

Our choices can be made with a growth mindset to make the most of an indeterministically-perceived future -> Behavioral Psychology

Our choices can be made with appropriate judgments in the decision moment -> Stoicism

What I am calling “free will” is a function of the wild volatility that creates an environment behaving with what we perceive as indeterministic in the moments that follow. Our perception of free will empowers our choices in a world with deterministic features and wild volatility. If we perceive the world as fixed or pre-wired by determinism, we are less likely to own and energize those high-influence choices impacting our future.

Depending on where one falls on the free will vs. determinism question, our past path to the present may have been impacted by free will, determinism, or some combination of both. However, regardless of that past path source, it is the quality of the choices we make in the present that will impact our outcomes in the indeterministic future.

As such, individuals can greatly help themselves by improving their decision-making ability and by frequently updating beliefs as new information is realized.

Now, a strict determinist would say – “If you did improve your decision-making ability, it was because of a complex web of determinist physics, environmental factors, and behaviors that made this better decision moment inevitable. It was not an actual choice based on free will.”

My response is, “It does not matter the source of that choice to learn better decision-making. I am glad you read this article! Do your best to choose better decision-making processes. Plus, tell other people as well. Think of yourself as a pebble being dropped in the pond of good decisions. The more and bigger the pebbles then the bigger and more frequent the emanating waves of good decisions will occur.”

In the article, How to create your own opportunity: The garbage picker’s choice, a case study is provided to show how all people may access our choices to change our future.

N.N. Taleb does a nice job describing life’s inevitable volatility. Taleb said: “Some things benefit from shocks; they thrive and grow when exposed to volatility, randomness, disorder, and stressors and love adventure, risk, and uncertainty.” We can take advantage of that inevitable volatility via our relationships with things that benefit from volatility. In mathematics, those things are known as inputs to convex transformation functions. [xiii]

1) We can identify things that expose ourselves to those volatility-benefiting convex functions. The time value of money, maintaining long-term healthy behaviors, and intentional exposure to serendipity are examples of such convex functions. As an example, Taleb suggests one of his favorite pastimes is "flaneuring," which is his way of exposing himself to the convexity benefits of serendipity. Thus, flaneuring is an input to the serendipity convex transformation function. This is just like savings are an input to the time value of money convex transformation function and healthy habits are an input to our long-term health convex transformation function.

2) We can and should make choices that take advantage of inevitable upside volatility and protect us from the ruin associated with inevitable downside volatility. In the personal finance world, dollar cost averaging by consistently investing in well-diversified growth portfolios is an example of a convex function that takes advantage of upside volatility and protects us from the ruin associated with downside volatility. [xiv]

The idea of this graphic is that our choices matter. While we can completely control almost nothing, we can influence virtually everything. In a world of wild volatility, we can think of our decisions as a portfolio of many choices, with each one influencing the probabilistic outcome of those decisions. Physicist and ergodicity expert Luca Dellanna said [xv]:

"The best strategy depends on whether you are the gamble or the gambler"

The gamble vs. gambler metaphor applies to our day-to-day choices. A good decision-maker seeks exposure to the upside - such as frequent, relatively small investments in health or savings. This is a gambler's behavior. All the while, minimizing or insuring against catastrophic downside - by using strategies including diversified investments or high deductible medical insurance. This is a recognition of an individual gamble's downside. The little bell curve on each path indicates we do not know for sure how we will reach the next node. We may not know which of those good green or red outcomes we will achieve. However, by exposing ourselves to convex functions and a good decision process, we increase our confidence that the green or positive outcomes will increase over time, the red or negative outcomes will stay small, and the net sum of all those outcomes will increase in value over time.

Why the free will v determinism question is a good question. (but still leads us back to why it is the wrong question!)

Thus far, our focus has been on what economists call ”Positive Economics.” That is, assessing the world as it is. The answer to “Why the free will v determinism question is the right question” will now divert away from positive economics. We now explore the realm of policies for how we change the world if we do not like it as it is. Through laws, social programs, and other human interventions, we cross into the policy world of “Normative Economics” or “so, what do we do about it?”

Regardless of the degree to which free will and determinism impact our decisions in the present, the deterministic factors we mentioned earlier certainly exist. Strict determinists make a good point because people have no control over those deterministic factors. As such, how can people be held accountable if they have little ability or agency to impact those deterministic factors? For example, our genome, hormones, and neurobiology are almost completely a result of our parents and early childhood conditions. Adults have no ability to “rewind the tape” and undo those factors in the present. Next are a couple of examples:

Criminal Justice: This deterministic thinking could certainly impact criminal justice policy. Clear punishment guidelines may make sense to discourage people from choosing a criminal action. However, a determinist suggests the individual had little choice based on their priors, thus a regime of rehabilitation and training makes good sense. So, if we “lock ‘em up” without rehabilitation, we are only reinforcing the priors creating the criminal predisposition in the first place. When unrehabilitated criminals are released from prison, we should expect nothing else than recidivism.

Systemic bias in banking data: Deterministic thinking also impacts credit policy and how we think about assessing people’s credit. Traditionally, the FICO score assesses a credit applicant’s ability to repay a loan in the future. This is accomplished by evaluating the credit applicant’s past payment behavior. At its core, usage of the score assumes a one-way causality arrow. That one’s past payment behavior will CAUSE their future loan performance. However, the determinists argue, with good effect, that people’s past data and performance were CAUSED by a lack of opportunity and their priors. Thus, to the determinist, the causality arrow is reversed. One's lack of opportunity CAUSES poor payment behavior. The systemic bias in the data used for the FICO score is a result of using a subset of banking data only representing that lack of opportunity. A broader source of data, including data traditionally outside the banking system, like utility payments or rent payments, will create a more fulsome picture and help correct systemic bias found in the bank-only data.

These are relevant “so what do we do about it?” questions and suggestions. There are certainly many more. These are for policymakers to debate. Naturally, there are different perspectives, usually divided into political party camps and other organizations attempting to affect change. The implications of what to do about it are beyond the scope of this article.

However, circling back to the “Why the free will v determinism question is the wrong question,” this brings us to one observation upon which stoic philosophy would agree. That is: Focus on what you can control. In the dichotomy of control framework, those are our choices and judgments TODAY. Since most of us are not policy makers, we have little control over policy, other than our vote. This leaves us with practical success advice:

Focus on what we can control, like choices and judgments

To get the most out of those choices and judgments, develop and grow a high-quality decision process.

Resources

To put a finer point on an essential Stoic teaching → It is our judgments of something that often lead us astray, not the thing itself. So if something “bad” happens, we tend to assign “bad” to the thing. A grounded Stoic appreciates it is the judgment that relates to assigning “bad” not the thing itself. The thing is just a thing.

For example, if an investment goes down in value, we may consider the investment as “bad.” It may or not be. The point is that it is our judgment that assigns it as bad, not the investment itself. In fact, the stock market is incredibly volatile and subject to broad randomness. Most investment price changes can only be explained by randomness. So, our quick “bad” judgment of a downward-moving investment is often wrong. We need a decision process that helps us overcome our quick-to-judge nature by better managing our judgments. The point is that our judgments have value but only in the correct context. Choice architecture, like Definitive Choice, provides that structure to make the most of our judgments.

Notes

[iv] Dweck, Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, 2006

[v] The Roman Stoic Epictetus introduces the dichotomy of control at the very beginning of his Enchiridion (Handbook).

Epictetus, Enchiridion, 125 CE

To be fair - Free will deniers do not dispute that people make “high influence” choices and judgments. The difference between free willers is that determinists don't believe people have independent causal agency over the physical matter in our bodies and brains. Thus, decision-making is both deterministic and "internally caused," rather than caused by an independent top-down process from a separate consciousness.

Thanks to Brian Klaas for his input on this clarification.

[vi] Seth, Being You: A New Science of Consciousness, 2020

[x] Klaas, Fluke: Chance, Chaos, and Why Everything We Do Matters, 2024

[xi] Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow, 2011

[xii] Hulett, Becoming Behavioral Economics — How this growing social science is impacting the world, The Curiosity Vine, 2023

[xiii] Taleb, Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder, 2012

[xiv] Hulett, Achieve Personal Finance success with a little math intuition, The Curiosity Vine, 2023

[xv] Dellanna, Ergodicity: Definition, Examples, And Implications, As Simple As Possible, 2020

Comments